Time to read

Puncturing the rubber romance

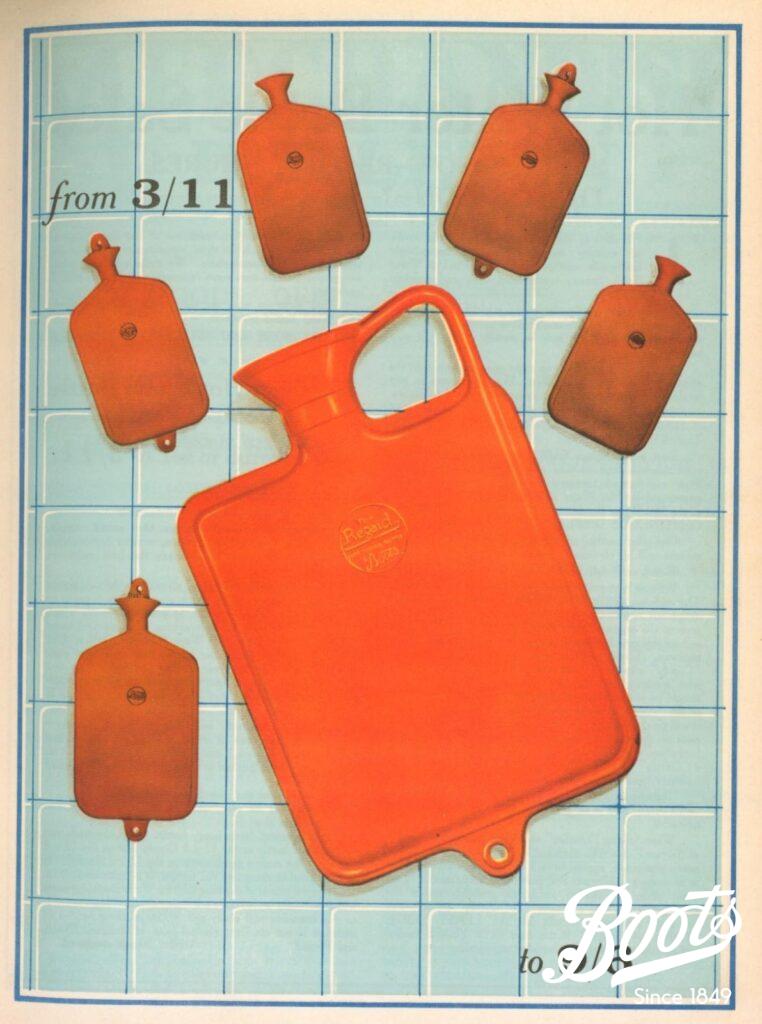

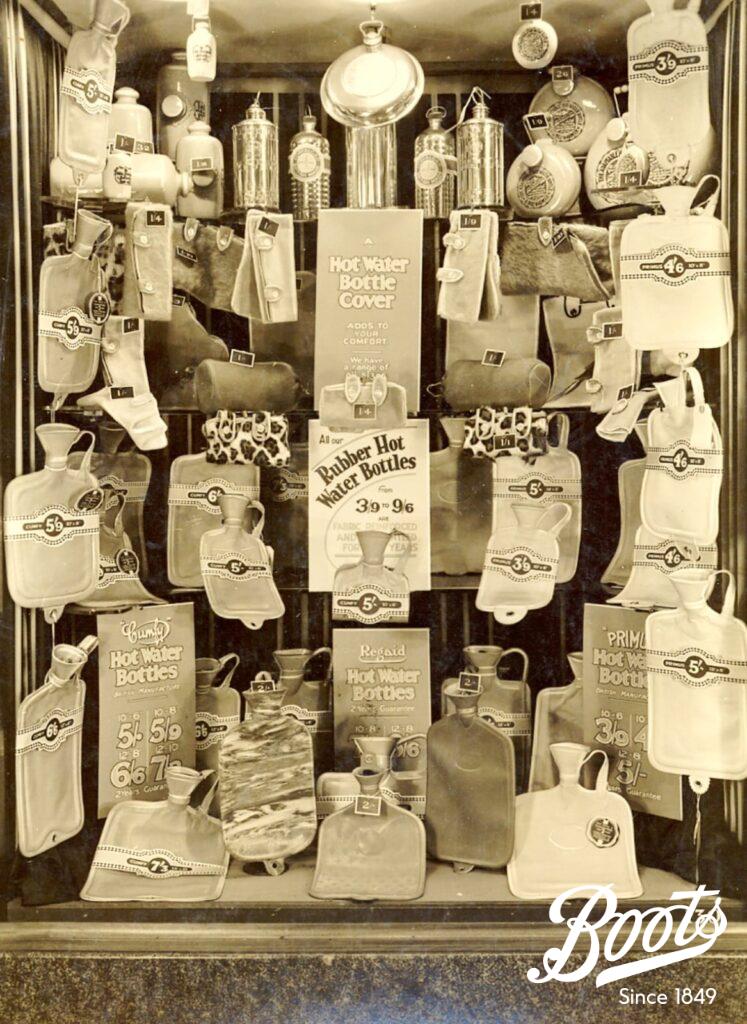

In the 1920s Boots was especially proud of its extensive rubber hot water bottle range. It stocked an impressive variety with models suitable for all price brackets. At the top of the collection, introduced in 1923, was the ‘Regaid Super Red’, finished in America by the New Haven Seamless Rubber Company.

In the 1920s Boots was especially proud of its extensive rubber hot water bottle range. It stocked an impressive variety with models suitable for all price brackets. At the top of the collection, introduced in 1923, was the ‘Regaid Super Red’, finished in America by the New Haven Seamless Rubber Company.

This emperor of hot water bottles was packaged in an attractive box, boasted a smooth finish without ridged seams, and had a larger funnel neck for ease of filling. Also fashioned in red, but priced more cheaply, was the locally made ‘Cumfy’. This was Boots’ most popular model. Sales staff were instructed to advise customers that, despite the competitive price, this was a ‘high-grade’ product made from ‘good quality, light-gravity rubber’. Cheaper still was the practical, no-frills, bottle: the ‘Perfection’ available in grey. Customers unable to afford even the ‘Perfection’ were recommended the bottom-of-the-range ‘Primus’. This was said to be a reliable, but very basic bottle, described in Boots’ own staff magazine as low-grade and ‘drab’.

In historical context, it is unsurprising that rubber hot water bottles were promoted as exciting, sales-worthy products. The period between the turn of the twentieth century and the end of the Second World War was the golden age for the global manufacture of rubber. As early as the 1770s, English chemist Joseph Priestley had discovered that a chunk of unrefined rubber could erase lead pencil marks. In 1824, the first Macintosh was sold, after Charles Macintosh invented a process for waterproofing fabric via a super-thin layer of rubber. The biggest period of rubber development, however, occurred after 1888, when Scottish veterinary surgeon, John Dunlop, invented the first pneumatic tire. The comfort this provided for bicycle riders was so transformative that within a decade, pneumatic tires started to be used on automobiles. The tire industry boomed, as demonstrated by the establishment of two leading rubber manufacturers: Michelin (France) and Goodyear (USA). These, along with a proliferation of smaller companies, created a huge demand for rubber, whose mass production was well underway by 1900.

Yet it was, perhaps, the smaller consumer items which felt the most transformative within people’s everyday lives. Rubber brought a whole host of mass-produced objects that were soon taken for granted: knicker elastic, rubber sheets (a great help for bed-wetters), swimming caps, and rubber teats for babies’ feeding bottles. In the realm of health and hygiene, rubber’s waterproof capabilities lent it great potential in the promotion of hygienic practises. Rubber items were watertight and could be wiped down, keeping them free from smells, unwanted fluids, and germs. Rubber, in short, was an exciting new medium to sell ‘modern’ hygienic standards within the British home. Boots may have prided itself on its hot water bottles, but this was only the tip of the rubber iceberg. Rubber products were produced in abundance during the 1920s with the company particularly promoting rubber gloves, elastic trusses (for lumbar support), and enema tubes. Even the first aid plaster became rubberised. A 1923 article on Regaid Adhesive plasters in the Boots’ staff magazine, was keen to point out their multipurpose capabilities. You might use them to dress a skin cut, but they were also claimed to be effective for fixing lids shut, for repairing leaky radiators or broken windows, and (bizarrely) for holding together cracked eggs. Contraceptive devices were another great area of innovation in the 1920s. Rubber was a vital ingredient in the production of diaphragms and cervical caps, and, in the form of very thin latex, of condoms— Yet Boots’ strong Methodist roots meant that the company refused to stock or promote such items. For Chairman, John Boot, it was clearly indecent for a male customer to ask for such items from a young, single salesgirl.

Few of Boots’ customers or staff would have appreciated the complex transnational stories that underlay these relatively banal items of convenience. Even though these goods were advertised as made of ‘Indian’ rubber, the rubber of their production very rarely came from India. The story of ‘British’ rubber products begins in the Amazon Basin. At the end of the nineteenth century, Brazilian seeds were brought back to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, where some were successfully hot-housed and then germinated. It was these seedlings that were then transported out to the outposts of the British Empire in Southeast Asia, which had suitable tropical climates. They were planted most frequently in Malaya (now Malaysia), Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Singapore, where Britain developed its biggest, most profitable, rubber plantations.

These plantations would have been overseen by a British plantation owner. As historian Stephen L. Harp details in his book, A World History of Rubber, migrant indentured labourers would have dug the holes to plant the seedlings and tapped the bark on the trunks of the mature trees, collecting the dripping latex into cups. These were then tipped into large vats, where the latex would congeal and become ‘rubber’. Once hardened, it was cut into sheets and hung to dry. It was in this state that the sheets would then be shipped to the UK or to the United States, where they would be made into consumer items in factories. From 1913 rubber could also be transported as liquid latex, which allowed for the production of stronger and thinner products in the UK and the US.

As with many raw materials sourced from the Empire, the structures of labour exploitation and racial inequality on which rubber extraction depended were rarely acknowledged in Britain. In the Boots’ staff magazine from 1923, for instance, an article on hot water bottle manufacture euphemistically referred to the overseas rubber industry as ‘one of the romances of the world’. The article did admit that rubber production meant ‘extreme riches’ for some and ‘intense human suffering’ for others, but the detail of this system was passed over quickly. As in many British articles about imperial raw materials, the authors took refuge in a romanticised history of early rubber prospecting, in which heroes made discoveries in the safer past tense.

By the end of the 1940s, the golden age of rubber was over. During that decade both Malaya and Ceylon gained independence from Britain, and British access to rubber was severely restricted. Furthermore, new synthetic materials, largely produced in the USA, became the focus of the future. Although natural rubber was still preferred for certain things, chemically manufactured synthetic rubber and plastics took over. But during the 1920s and 30s when, at the height of Empire, British interests controlled about 75% of the global rubber trade, systems of exploitation underpinned almost every rubber commodity sold in Great Britain. This disquieting global story may seem at odds with the benign and comforting image of the domestic hot water bottle, but such contradictions are commonplace within histories of global trade.